The big picture

The Rasmussen lab uses zebrafish to gain molecular and cellular insights into neuronal and tissue plasticity, both during development and following injury. The skin is our largest sensory organ and is densely innervated by somatosensory nerve endings that sense pain and touch. Nerve regeneration is often incomplete following skin injury, and sensory loss is a major complication associated with diabetes and chemotherapy. Using the imaging advantages of the zebrafish system and novel remodeling assays developed in the lab, we have identified interactions between somatosensory nerve endings and several specialized cell types (including osteoblasts, resident macrophages, and mechanosensory cells) within the skin tissue environment. We are currently pursuing the following related projects:

- Control of nerve patterning during skin development and regeneration

- Maintenance of skin homeostasis by resident phagocytes

- Development, regeneration, and function of mechanosensory cells

Why zebrafish?

Whereas many of the key events in skin and somatosensory development occur in utero in mammals – making them relatively inaccessible – the external development of zebrafish allows for facile observation and manipulation of maturing skin. The Rasmussen lab uses the genetic and imaging advantages of zebrafish to study nerve remodeling in a living vertebrate with single-cell resolution. Since zebrafish can regenerate almost any adult structure (Rasmussen and Sagasti, 2017), they are an excellent system for identifying mechanisms of successful nerve and tissue repair.

Project 1: Control of nerve patterning during skin development and regeneration

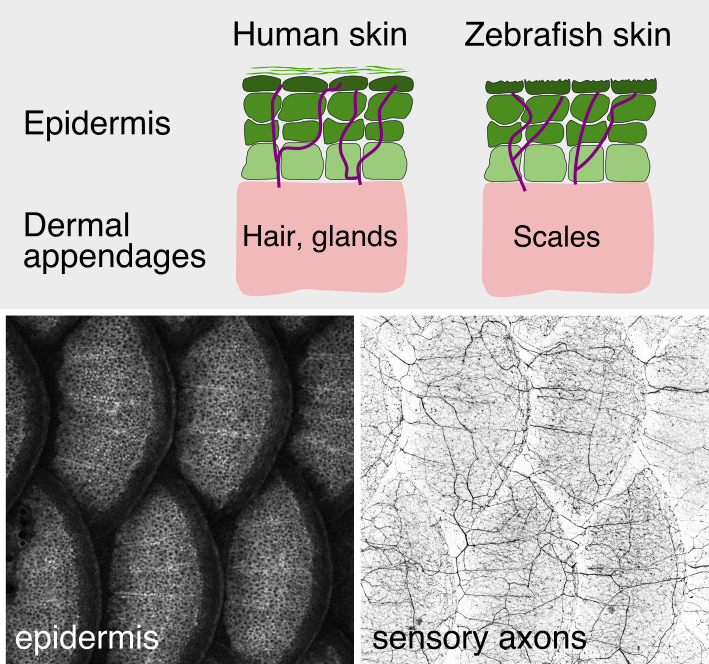

As animals mature from embryonic to adult stages, the skin grows and adds epithelial

strata, specialized cells, and dermal appendages (e.g., hairs, feathers, and scales) (see

figure). How somatosensory nerves adapt to these dramatic changes in their target tissue is poorly understood. By examining juvenile fish, the lab previously discovered that skin innervation dramatically remodels following scale development. In contrast to the simplified larval innervation pattern, which is driven by growth and repulsion of naked axon endings, adult axons enter the epidermis as evenly spaced nerves, suggesting an alternative mechanism for spacing axon endings in adult skin. Surprisingly, a subset of dermal osteoblasts involved in scale formation independently guide nerves and vasculature during development and regeneration (Rasmussen et al., 2018). Our analysis of cellular interdependence also revealed roles for osteoblasts in patterning endothelium and somatosensory axon innervation during caudal fin development (Bump et al., 2022). These results suggest that dermal osteoblasts function as central organizers for these other tissue types the development of multiple skin regions. We are currently investigating the mechanisms that regulate osteoblast patterning of nerves and vasculature.

As animals mature from embryonic to adult stages, the skin grows and adds epithelial

strata, specialized cells, and dermal appendages (e.g., hairs, feathers, and scales) (see

figure). How somatosensory nerves adapt to these dramatic changes in their target tissue is poorly understood. By examining juvenile fish, the lab previously discovered that skin innervation dramatically remodels following scale development. In contrast to the simplified larval innervation pattern, which is driven by growth and repulsion of naked axon endings, adult axons enter the epidermis as evenly spaced nerves, suggesting an alternative mechanism for spacing axon endings in adult skin. Surprisingly, a subset of dermal osteoblasts involved in scale formation independently guide nerves and vasculature during development and regeneration (Rasmussen et al., 2018). Our analysis of cellular interdependence also revealed roles for osteoblasts in patterning endothelium and somatosensory axon innervation during caudal fin development (Bump et al., 2022). These results suggest that dermal osteoblasts function as central organizers for these other tissue types the development of multiple skin regions. We are currently investigating the mechanisms that regulate osteoblast patterning of nerves and vasculature.

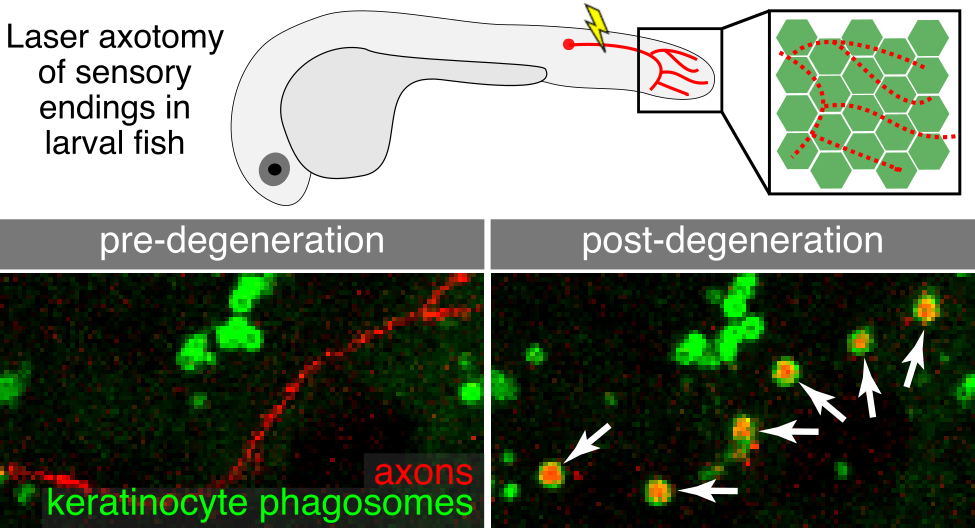

Project 2: Maintenance of skin homeostasis by resident phagocytes

The skin is our primary barrier to the external environment and faces constant environmental insults (e.g., injury, ultraviolet light). Injury or disease states can trigger axon degeneration leading to a loss or dysregulation of sensory function. Understanding how the skin responds to axon degeneration may be relevant for strategies to restore sensation. Our earlier work in larval skin found that keratinocytes engulf degenerating axon debris (Rasmussen et al., 2015) (see figure). To ask whether the more complex adult skin uses similar or different mechanisms, we established assays in adult zebrafish to track degenerating axons with high resolution. Our live-imaging revealed a previously unknown role for Langerhans cells, a type of skin immune cell, in removal of axon debris. Surprisingly, adult keratinocytes were unable to compensate for the removal of Langerhans cells (Peterman et al., 2023). This research uncovers a critical new function for immune cells in skin sensory repair. We are extending these studies to understand the cytoskeletal mechanisms that allow Langerhans cells to navigate the skin, engulf axon debris, and ultimately degrade this debris.

The skin is our primary barrier to the external environment and faces constant environmental insults (e.g., injury, ultraviolet light). Injury or disease states can trigger axon degeneration leading to a loss or dysregulation of sensory function. Understanding how the skin responds to axon degeneration may be relevant for strategies to restore sensation. Our earlier work in larval skin found that keratinocytes engulf degenerating axon debris (Rasmussen et al., 2015) (see figure). To ask whether the more complex adult skin uses similar or different mechanisms, we established assays in adult zebrafish to track degenerating axons with high resolution. Our live-imaging revealed a previously unknown role for Langerhans cells, a type of skin immune cell, in removal of axon debris. Surprisingly, adult keratinocytes were unable to compensate for the removal of Langerhans cells (Peterman et al., 2023). This research uncovers a critical new function for immune cells in skin sensory repair. We are extending these studies to understand the cytoskeletal mechanisms that allow Langerhans cells to navigate the skin, engulf axon debris, and ultimately degrade this debris.

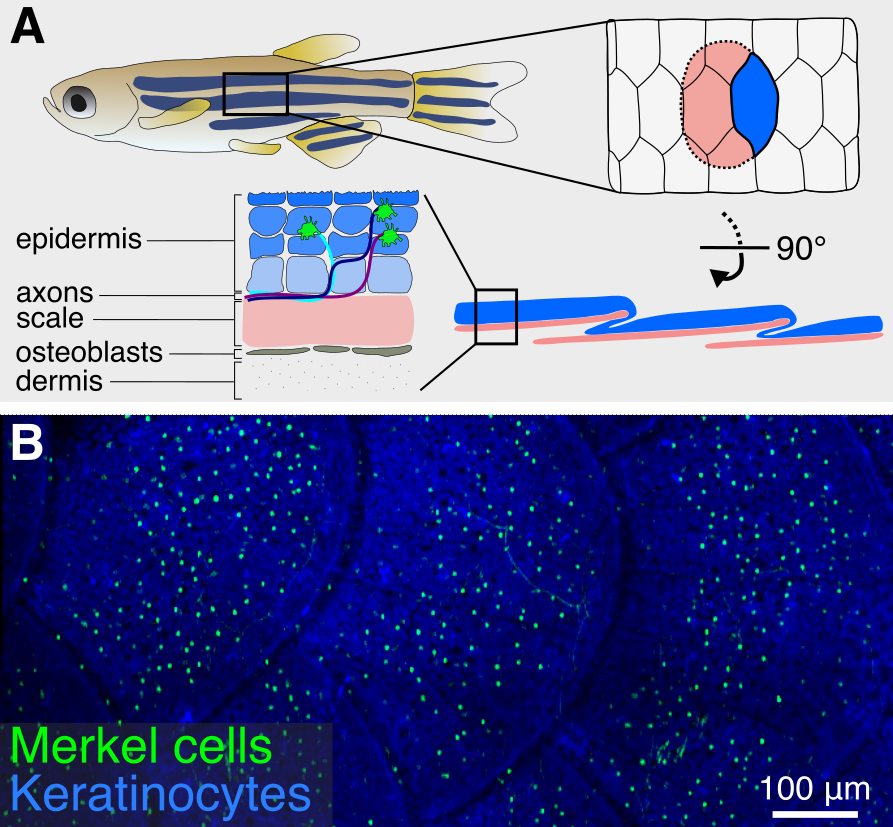

Project 3: Development, regeneration, and function of mechanosensory cells

Merkel cells are sensory cells found in the vertebrate epidermis that detect object curvature and texture. Over the past several decades, the development and function of Merkel cells has primarily been studied in rodent systems. While these studies have been fundamental for understanding how Merkel cells regulate somatosensory responses to touch, the in utero development of rodent embryos limits access to key stages of Merkel cell development, leaving several unanswered questions. Ultrastructural analyses have identified Merkel cells in a wide range of fish and amphibian species with externally developing embryos, but in-depth investigation in these systems has been hindered by a lack of genetic reagents to label the cells. We recently identified a previously uncharacterized population of cells in the zebrafish epidermis that share key molecular, cellular, and developmental properties with mammalian Merkel cells (Brown, Horton, et al., 2023). Based on our analysis, we propose that these are bona fide Merkel cells. Importantly, we describe genetically encoded tools that allow for non-invasive imaging of Merkel cells in living animals. We are currently developing genetic and functional assays to probe unanswered questions in Merkel cell development and regeneration.

Merkel cells are sensory cells found in the vertebrate epidermis that detect object curvature and texture. Over the past several decades, the development and function of Merkel cells has primarily been studied in rodent systems. While these studies have been fundamental for understanding how Merkel cells regulate somatosensory responses to touch, the in utero development of rodent embryos limits access to key stages of Merkel cell development, leaving several unanswered questions. Ultrastructural analyses have identified Merkel cells in a wide range of fish and amphibian species with externally developing embryos, but in-depth investigation in these systems has been hindered by a lack of genetic reagents to label the cells. We recently identified a previously uncharacterized population of cells in the zebrafish epidermis that share key molecular, cellular, and developmental properties with mammalian Merkel cells (Brown, Horton, et al., 2023). Based on our analysis, we propose that these are bona fide Merkel cells. Importantly, we describe genetically encoded tools that allow for non-invasive imaging of Merkel cells in living animals. We are currently developing genetic and functional assays to probe unanswered questions in Merkel cell development and regeneration.